In late-Victorian Britain, Australia and less commonly, the United States, baby farming was a practice involving taking custody of a baby in exchange for payment, either in the form of a lump sum or continuous ongoing payments.

Women and couples who had babies out of wedlock in the 19th century didn’t have many options. They couldn’t just “keep” their children. They sold their babies to baby farmers. They were allowed to visit, if the mother’s chose that option. This sort of arrangement wasn’t all that uncommon in the 19th century. To rid the problem of illegitimate children, some women would resort to birthing their baby and leaving it somewhere amongst the elements or having backyard abortions. Others hid their pregnancy and would attempt to find them a new home, to give them a good life, better than they could. It wasn’t rare to find ads in the newspaper consisting of women looking for people to take their children. Whatever their avenue, prevailing morality was above keeping an illegitimate infant.

This book was fascinating, but it is extraordinarily thorough and very dense. Reads like a history book and had some extensive family tree layouts that were tough to follow. The author was super authoritative on this subject, so I absolutely recommend this book, but I did require a few breaks here and there. Because it’s such a fascinating subject, I decided to write this blog to explain this particular case of baby farming further, because I’ve also done my own research as well.

Sarah and John Makin were not the only baby farmers in 19th century Australia and not the only ones on trial and even executed for their crimes. In total, 13 babies were found buried in the backyards of the Makin’s various homes. There were several women in the late 1800s tried and executed for the practice of baby farming throughout Britain and New Zealand.

Of all the babies found, there was only one infant that they were able to prove was killed by the Makin’s, Horace Murray. So, while they were on trial for one child, the other 12 dead babies in their yard certainly didn’t help their case. The 18-year-old mother testified she gave the Makin’s ongoing child support payments and her baby was sold to them healthy. She made several attempts to visit the child but was continuously met with excuses, and his body was one of 13 found buried.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, babies often died from disease, syphilis, malnourishment due to impoverished parents/guardians or overdosing on Soothing Syrup. A lot of the women who became pregnant were casual prostitutes, a job that many unwed women took to in order to make ends meet. And during encounters, contracted syphilis. Therefore, many of the newborns eventually died from the disease in the care of the baby farmers. Because the babies were so badly decomposed at the time they were found, it was nearly impossible to conduct proper autopsies to determine a cause of death.

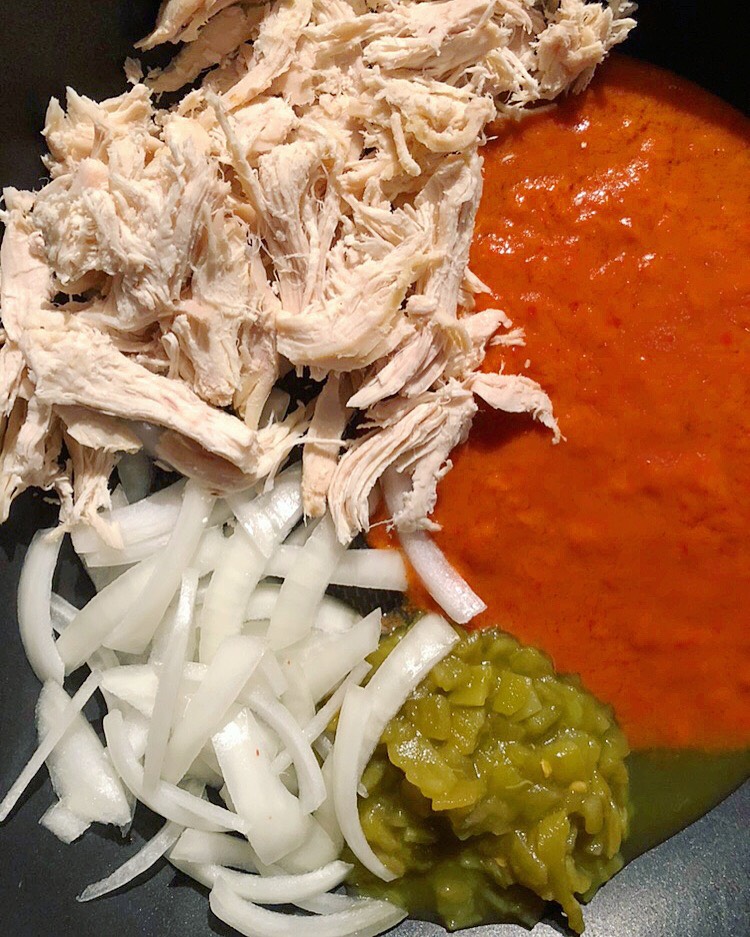

Soothing Syrup or Godfrey’s Cordial was a commonly used OTC “medicine” containing opium. And frequently used by mothers to sedate a fussy baby or help with diarrhea or colic. Also, those in poverty used it since it was cheap and would keep babies from crying when they were hungry, which is why many babies became malnourished. People would also water down baby formula if money were tight. The convenience, accessibility and low cost made Soothing Syrup an ideal choice used by baby farmers. Children often died from overdoses, which can explain the high infancy mortality rate for the babies that farmers oversaw.

The jury was only able to go off testimony from the women who came forward, willing to look at photographs and clothing that the babies were buried in to help identify them. Many of the women had in their contracts the right to visit their babies weekly, but the Makin’s typically had an excuse why they couldn’t see the baby, indicating it was already more than likely dead. It was all based off circumstantial evidence. But 13 babies buried on their various properties, isn’t just a coincidence, and highly unlikely they all died of natural causes with zero foul play. Especially since the Makin’s were known to have criminal records as well struggle financially. But for the times, people did what they had to in order to survive, no matter how morbid.

To that point, they were also shady with the money they received. Parents would have to either give a lump sum to the Makin’s or weekly payments to help support the babies. It was never enough to fully care for a child, but it is expected that the couple pocketed the money and resorted to cutting corners to care for the child, like all baby farmers, by watering down formula or using Soothing Syrup frequently. Many mothers testified they turned over healthy babies, which was often written in contracts, and when they would visit, their baby would look thin, frail and ill. Even coroners reported the remains of the babies looked extremely malnourished.

Again, it wasn’t uncommon for babies to die from several causes in that era, so when the Makin’s would inform parents their baby had died, they’d ask for a burial payment. Most parents didn’t ask questions about why the child died since the rate of infant deaths was fairly high during that time. They said they would put the babies in a nice coffin or grave using that money. But, pocketed the fee and just buried the baby in the backyard. The smell coming from the yard was unmatched by anything anyone had experienced, witnesses said. And a worker discovered two bodies buried in the ground while attempting to fix a blocked underground drain near the Makin’s yard, and alerted authorities.

John and Sarah Makin were both convicted of murder. John was hanged in 1893 and Sarah was given life in prison, as executing a woman was not allowed at the time in Australia. John made several attempts to save his own neck, by saying baby farming was at the root a female practice, as nobody would sell an infant to a single man. Unwed mothers always looked for loving women to take their children. And the baby farming business he found himself in would never have come to be if it weren’t for his wife.

Misogyny was socially acceptable and John took every advantage he had to save himself. But he was the one in court who had no remorse, remained stoic. Sarah was crying, fainting, acting theatrical. Other witnesses said Sarah was a “bad woman” and brash, bold, defiant. She had a temper. The pointing fingers didn’t make much difference since they partook in the baby farming together, and the jury didn’t seem to care much about who was more at fault. John also seemed to accept his fate with composure when the verdict was read, most likely knowing that at least one of those babies died due to foul play.

What’s most fascinating is that these children mattered more in death than they did in life. The black market selling and murdering of babies was inevitable in impoverished Victorian society, there was a clash between poverty and morality. You could sell your baby, because women couldn’t raise illegitimate children, but if it died in the hands of the farmers, it became a crime. Babies were not always adopted healthy either, sometimes the mothers would attempt to care for them and sell them when they were several months old, requiring the female baby farmers to begin wet-nursing, breast-feeding done by a woman who is not the mother.

The truth behind the practice of baby farming is chilling. Young, unwed mothers were desperate, and the conditions of the time were heartbreaking. The social stigma of illegitimate babies in the 19th century had the capability to break even the most powerful bond there is, between mother and child, bringing to light a sobering reality from just over a century ago.